RealityCapture

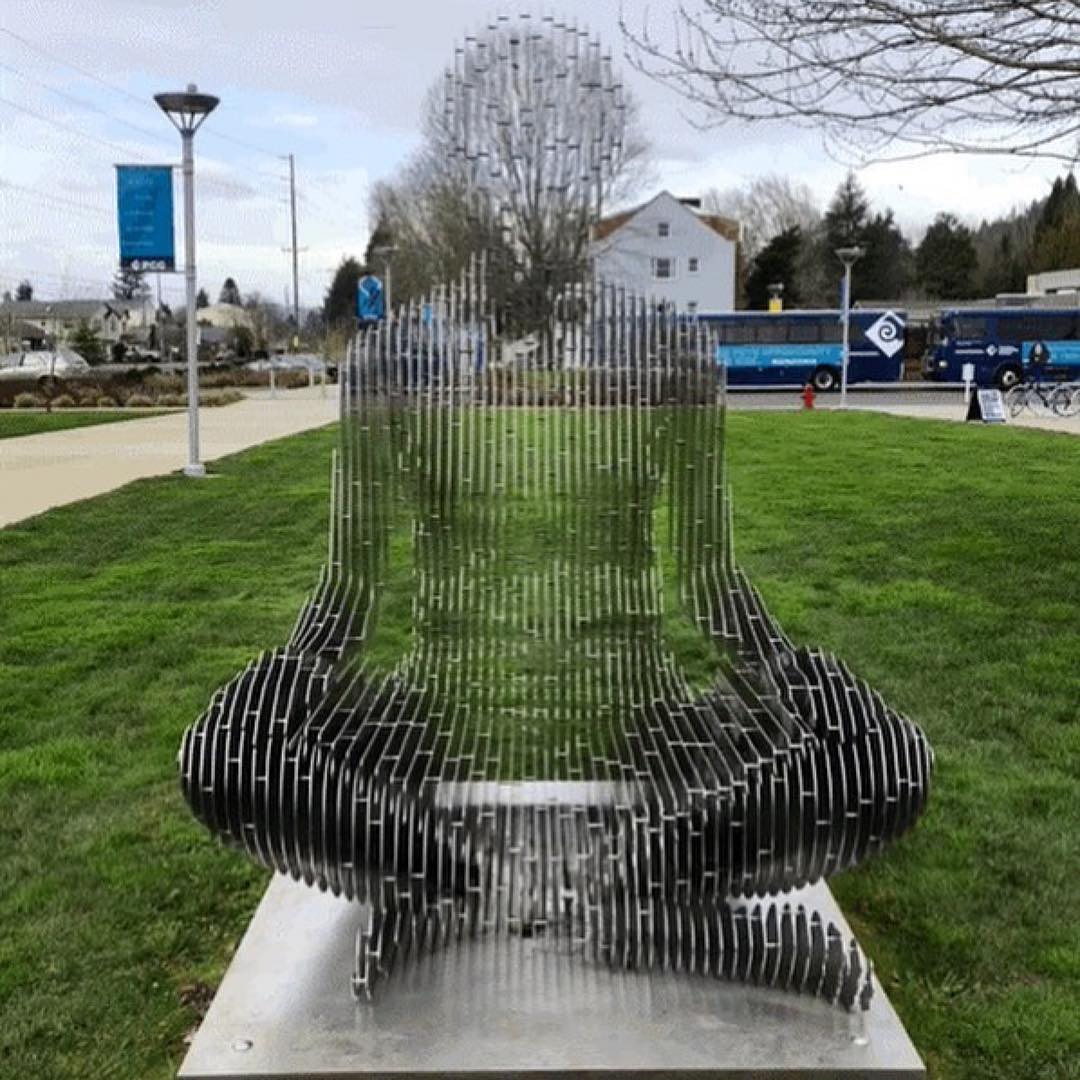

Sculptures disappearing into the air - Julian Voss Andreae

How did you get the idea to create disappearing sculptures? When did it all start?

The idea for my body of ‘disappearing’ sculptures was directly inspired by my work I had done as a physicist before I went into art. I studied physics at different European universities for a number of years and ended up doing my graduate research with Anton Zeilinger in Vienna, in a research group specializing on fundamental questions of quantum physics with a deeper philosophical interest.

We set out to show that even fairly large pieces of matter still behave as quantum mechanical waves and we used Carbon-60 molecules, the famous ‘buckyballs’, to do that. After this experiment was a success, I started looking into other, even larger candidates for such experiments – the crazy dream was to eventually be the quantum object yourself, getting sent as a wave and being detected again as a particle – how would that feel like?

That idea, to think of myself as a quantum object led in 2006 to the idea to create a stylized walking figure titled “Quantum Man”, consisting of parallel slices with gaps in between, arranged like the wave fronts in the quantum mechanical wavefunction that would describe that motion.

How has the technique you use for creating these statues evolved and why did you decide to use RealityCapture?

I made this first “Quantum Man” by carving the walking figure out of a large block of Styrofoam and then physically slicing it up with a knife. I then traced the shape of each slice onto steel to cut it out.

In later iterations, I photographed each part and traced the outlines on the computer to create files that allowed for CNC cutting of the metal.

Then I made some sculptures by creating physical figures which were 3d-scanned with early industrial structured-light scanners and sliced virtually. Those ATOS scanners were also what I used for my first 3d-scans of life humans in 2008. 3d-scanning was still very difficult and expensive then.

In 2012 I did my first photogrammetry life-scan, still in very low resolution with an early, now obsolete technology, and finished the first sculpture based on those data in 2016 – I loved the outcome and soon realized that the key was the high degree of global accuracy that made this technology able to capture something very subtle about the human body.

I built my own 3d-scan rig consisting of 170 “Raspberry Pi” computers with 8 Megapixel cameras and use RealityCapture to crunch the data because it seems the by far best and fastest such software. I am always still flabbergasted how RealityCapture achieves its results, making sense of so much information, and of such a ’fuzzy’ kind – I wouldn’t even know how to begin writing that type of code.

What makes the statue disappears?

The ‘disappearing’ works consist of parallel slices of metal with gaps in between them. Along the direction of the slices you see only about 10% of metal, but the rest of the visible area is open, revealing what is behind the sculpture.

In addition to this small fraction of metal visible at that ‘disappearing angle’, the polished stainless steel I often use, reflects the colors of the environment making the work blend in even more.

Viewed from any angle significantly different to that disappearing angle, the sculpture looks like solid metal, because the narrow gaps soon close the view through the sculpture as the viewer moves by.

So, the statues are actually real people 3D scanned?

Currently, much of my sculptural work is figure-based and almost all the ‘disappearing’ works start with studies using 3D-scans of a real human beings, these days either photogrammetry or structured light or a combination thereof.

But getting the data representing someone’s body into the computer is only the very beginning of a long journey of sculpting the overall shape in the computer, in a very similar fashion as you would in traditional techniques involving clay or stone.

In the next step I use an array of ready-made and custom written programs and algorithms to arrive at the object I envision. Sometimes I make 3D-prints and combine those with other portions modelled in actual clay and then re-scan to get that object into the computer for further tweaking. When I like the 3d shape, I virtually cut it up into 2D slices.

The next step is the most time-consuming portion of the process, namely turning the unappealing ‘polyline’-type part outlines into beautifully curved ‘Bezier’-type drawings. In that phase we add to the files all other information we need to successfully fabricate the sculpture – for example where the connecting pins are positioned, where the welds are on the baseplate, and of course all the part numbers so we can find our way through the giant puzzle.

Then the parts get laser-cut from sheets of steel, bronze, or titanium. Finally it is time for the fabrication process in my studio: hundreds of hours of welding, grinding, sanding, and polishing at a very high skill level.

What is the most challenging for you in the process?

The most challenging part is always the beginning, the struggle to realize a new idea: You have a vague vision of what you want to achieve but you are not yet able to fully see how it is going to look like, and certainly not able to show it to anybody else. There is only a faint sense that you are onto something important, something worth your time and energy. It is an uphill battle to keep pushing the realization of the vision, to convince people and to keep believing in your dream despite all the apparently good arguments, not to.

About

Voss-Andreae has been creating sculptural works directly influenced by his background in science, technology and art. He developed one of his signature styles of sculpture where the human figure has volume and weight when viewed from one angle and almost completely disappears at another. The human figures are usually real people scans that were captured with photogrammetry software RealityCapture. His work has been featured in print, broadcast media worldwide and recently won the prestigious CodaWorx award for public sculpture.